The battle of Kashmiri craftsmen to save a music heritage

BBC World World

Adil Amin Ahman

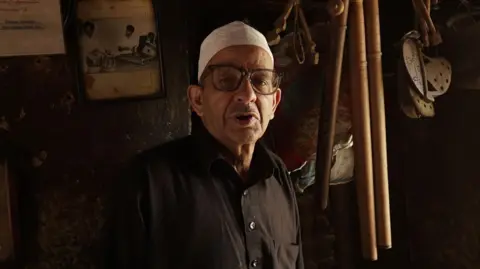

Adil Amin AhmanIn the quiet, narrow lane of Srinagar in Indian-Advanced Kashmir, a small, dark burned workshop is one of the last holdouts of the invisible craft.

Inside the shop, Ghulam Mohammad Jhaz is sitting, which is believed to be the last artisan of the region, which can make Santur hand.

Santur is a trapezoid-shaped string musical instrument, which is similar to a dulusim, which is played with malats. It is known for its crystalline-like tones, and has been the signature of Kashmir for centuries.

Shri Ghulam Mohammad is a descendant of Car craftsmen for making string instruments in Kashmir for seven generations. The name of the ZAZ family has long been synonymous as the makers of Santar, Rabba, Sarangi and Sehtar.

But in recent years, the demand for handicrafts has been reduced, changed by machine-made versions that are cheap and faster for production. At the same time, the taste of music has changed, which has reduced.

“Hip hop, rap and electronic music are reigning on the soundscape of Kashmir, while the younger generations will no longer connect to the room or discipline of traditional music,” says Shabir Ahmed Mir. As a result, the demand for Santur has dropped and the craftsmen have been released without training or sustainable market.

Adil Amin Ahman

Adil Amin AhmanIn the old shops of the century, Shri Ghulam Mohammed is sitting beside the hollow block of wood and tired iron tools – a quiet remnant of a disappearing tradition.

They say, “There is no one left (to continue crafts).” I am the last. “

But this was not always the case.

Over the years, Sufi and folk artists have played the Santos of the handcuffs by Shri Shri Mohammad.

In a photo of his shop, Maestros Pandit Shiv Kumar Sharma and Bhajan Sopori have performed with their instruments.

It is believed that Persia was born, Santar reached India in the 13th or 14th century and spread from the Central Asia and the Middle East. In Kashmir, this was a different identity and Sufi became the focus of poems and people’s traditions.

“Originally the part of the Sufiana Maile part (a combined music tradition), the soft, the soft, the tone of the people,” says Mr. Mir.

Pandit Shiv Kumar Sharma later converted to Indian classical music, he says, by adding wires, by re -designing the bridges for rich resonance and presenting a new play plane technique.

The hymns of Kashmiri Bhajan Sopori, “made your tenal range deeper and poured it with Sufi expression”, added by Mr. Mir and helped cement Santur’s place in Indian classical music.

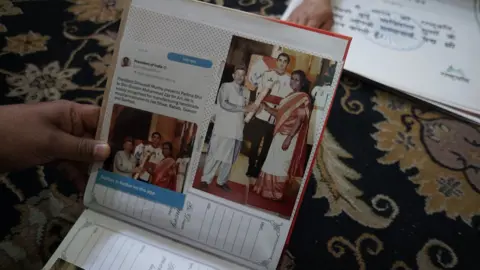

Mr. Ghulam Mohammad was seen in the second photo of Padma Shri from Padma Shri in the second photo of Draupad Murmu in the 5th and honored the performance of the fourth civilian award of India.

Getty

GettyMr. Ghulam Mohammad was born in Zaina Kadal in the 70s. The neighboring area in the name of this iconic bridge once served as a lifestyle of commerce and culture in Kashmir. As he grew up, he was surrounded by the voices and tools of his family trade.

He was forced to quit formal education at a young age due to health problems, and only when he started learning the art of making himself a santoor for his father and grandfather.

They said, “If they do not just teach me how to make a tool, how to listen – how to do wood, air and hands,” he said.

He says, “My ancestors were called by the courts of the local kings and often asked to build tools that calm the hearts.”

In his workshop, a wooden bench planted by the chisel and wires is on the side of an incomplete saint’s scallet frame. Old walnut wood is smelling the air, but there is no machinery at sight.

Shri Ghulam Mohammad believes that machine-manufactured equipment does not have the warmth and room of hand-stacked and the audio quality does not approach anywhere.

Making a santa is a slow, deliberate process, says the craftsman. It starts with choosing an adult and experienced proper wood for at least five years. The body is then carved and hollow for optimum resonance, and each of the 25 bridges is precisely shaped and kept.

More than 100 wires are attached, after which after the hard -working tuning process, which may take weeks or months.

He says, “This is the art of patience and perseverance.

Getty

GettyIn recent years, social media influencers have visited Shri Ghulam Mohammed’s workshop and shared his story online. He attracts attention, but says that it did not make real efforts to maintain crafts or her legacy.

He says, “These are good people, but what will happen to this place when I go?”

Since his three daughters pursued other careers, there is no family in the family to continue his work. In the last few years, he has offers – government grants, promises of teaching, even the suggestions of the State Crafts Department.

But Mr. Ghulam Mohammed says that he does not “find fame or charity”. He really wants him to take the arts forward.

Now in the eighties, he often spends hours on the side of the incomplete santur, listening to the silence of the one who has yet been completed.

“It’s not just woodwork,” he says.

“This is a poem. One language. I give the tongue I give to the instrument.

“I hear before playing santur. This is the secret. This is the need to move on,” he says.

Since the outside world accepts modernity, Shri. Ghulam Mohammed’s workshop remains untouchable from time to time – slow, calm and filled with walnuts and aroma of memory.

“Wood and music,” he says, “If they don’t give them time, both of them die.”

“I want a person who really likes crafts. Not for money, not for camera, but for music.”

Follow BBC News India Instagram, YouTube, Twitter And Facebook??

Post Comment